THE EXPEDITION TO APOLOBAMBA

Summary

The expedition lasted three weeks (April 16–May 6), during the southern

hemisphere fall. We worked in three different locations along the road

Charazani–Apolo between 800 y 2500 m elevation, in the Integrated Management

Area of the Apolobamba National Park (IMA). The principal objectives were to make

quantitative inventories for Alfredo Fuentes doctoral thesis in an area that so far

has not been studied in detail. We evaluated eight different types of forest, for

which we were completely lack information, in the montane seasonal forest and the

upper subhumid subandean seasonal forest. We collected 1200 vascular plants and 60

mosses and made 32 quantitative inventories in primary forest and five in secondary

forests. We collected a specimen of a Columelliaceae that was not know in the region

previously, several fertile Lauraceae previously collected sterile in other inventories

and Barnadesia woodii that until now was only known from the type.

Personnel

The expedition was led by Alfredo Fuentes with the collaboration of Fabricio Miranda,

thesis student in the project, Rubén Huanca and Pamela Mollinero, volunteers from

the agronomy school in La Paz. We were further accompanied by Ramiro Cuevas, Ever Cuevas y

Honorio Pariamo experienced guides who regularly works with us in the field.

The expedition…

We arrived in a four wheel drive LandCruiser rented with chauffeur from a company that

travels this route on a routinely basis. The road in the Apolobamba IMA follows for the most

parts the rivers Charazani and Camata in the deep valley surrounded by high mountain

ridges.

Locality 1: Seasonal Montane Forests

We first installed the quantitative study plots, and then we collected generally in the area

between 2000–2500 m, an elevation where few studies has been done so far in the region.

This elevation has in many areas been completely transformed through human activity stemming

back from pre-Colombian times, the forest are today restricted the steepest slopes in some places

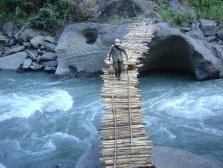

we had practically to climb the bluffs and in others we had to cross the strong currents of the

Charazani or Camata River on foot or with the help of the cable bridges locally called

“maromas”. The access to the other side, where the grass is always greener, was

difficult because of the lack of fords and well constructed bridges.

They are made by the people in the area and without doubt civil engineers were

not consulted. It requires a cool head and no fear of heights to cross the flimsy wooden

trunks that constitutes the bridges surface. What will they do when there are no more trunks

to repair and maintain the bridges?

The forest are composed by small trees and shrubs particularly of the genera Hedyosmum,

Miconia (several species), Berberis, Columellia, Duranta and

Nectandra, frequently with large entanglements of the Andean bamboo Chusquea in

the more open areas, and ferns and mosses dominates the under story. In a remnant of forest near

the Carpa community the dominating species belonged to Lauraceae and Myrtaceae a surprising

composition that may indicate a similarity to the “Myrtaceae forests” from cooler

climates of the Tucumano–Bolivian forest south of the knee of the Andes.

The people living in the area belong to the Quichuas language group. The main urban settlements

and larges population densities are found in the cities of Camata and Chrarazani located at the

limit between Puna and the dry to humid valleys of the Yungas Bolivianos. Currently there is a

constant slow migration towards unoccupied or less occupied areas at lower elevation; they open

up fields on very shallow rocky soils clearing the forest even on the steepest slopes that are

very inapt for agricultural purposes.

Locality 2: Seasonal subAndean Forests

The second locality was located is seasonal subAndean Forest at 1200–1700 m elevation. The

preservation of intact vegetation was also here difficult to find and in almost all the sites we

could access we found clear indications of alterations. To our surprise we found several

“pircas” or human constructed rock walls up to about 2 m in height and others stone

constructions that we do not know the function of. We are speculating that these constructions

may belong to the “Mollo” culture the builders of the city of Iskanwaya one of the

largest archelogical sites in Bolivia. We were profoundly surprised by the extent of the wall

system which we interpret as part of a complex system of terraces build to facilitate agriculture

on the steep slopes.

|

The forest of this area contain typical elements from what has been called the

“Pleistocene Dry Forest Arc,” it is dominated by species as Cedrela sp,

Luehea sp., Maclura tinctoria, Astroniumurundeuva,

Anadenanthera colubrina, Trichilia spp, Machaerium pilosum,

Maytenus sp. These forests are different from other dry forests in the region, as

for instance those found in the Tuichi river valley, because species with small leaves

(microphylous) are few (number of species) and rare (few individuals). As far as we know this

forest type has not previously been inventoried or even mentioned in the literature.

We camped at Marumpampa and Siata located at 1200 m, and from there we managed to reach montane

pluvial and seasonal forests up to about 2000 m of elevation. We had to scale rocky slopes to get

there and we needed all the help we could get from the local guides. In Siata a local guide helped

us to find an old trail used by the “incienceros,” people who collect the resin of a

species of Clusia sp. to sell it for commercial use as incense. This trail allowed us to

access to the higher elevations and to evaluate the forests above 2000 m elevation where we spend

a very cold night. This area was interesting, it was well preserved and many typical Andean elements

were found as Weinmannia spp, Ilex spp, Ericaceae spp. y Podocarpus cf.

ingensis, and numerous species were found fertile even in the plots.

|

From here we moved on to the village of Majata where we expected problems with the local villagers.

They are very zealous and problematic; they are particularly suspicious of all outsiders whom they

suspect to be antinarcotics agents that are only interested in gathering information about their

cultivation of illegal Coca, which have increased considerably in the last years.

The majority of the inhabitants that live in and around the protected area also have a bad impression

of the National Park and the conservation activities. This misperception and misunderstanding often

lead to conflicts and minor incidents with park guards and researchers who visit the area, and as

predicted we were negated access by one community.

Locality 3: Submontane Pluvial Forest

Finally we worked in a zone where the forests were dominated by the Andean palm Dictyocaryum

lamarckianum in the upper area about 1200–1600 m and the Oenocarpus bataua in

lower areas, 800–1200 m elevation. This locality has the largest, best conserved and most

diverse forest of the Apolobamba IMA. This area receives high levels of precipitation and is often

covered in fog and the road turns into mud and make it completely impassible during the rainy

season.

The forests are very interesting, we hypothesize that the vegetation represent Amazonina elements

that have reached these interior Andean area and diversified significantly. We have found numerous

endemic species here of genera that are typically Amazonian genera such as Parkia,

Hevea, and even the Brazil nut Bertholletia excelsa. Unfortunately the area is

gradually being occupied by “colonos” who cut down the forests to grow coca and the

future of this ecosystem far from secure even inside a protected area.

|